Shapes

The Centered Keyboard

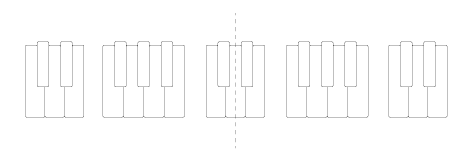

Shapes uses the keyboard both as a diagram for representing collections of notes that fit together, and as a playable instrument. But the keyboard in Shapes looks a little different than a standard keyboard.

For one thing, it doesn’t have black and white keys. All the keys are the same color, and they’re differentiated only by whether they stick up (the top keys) or don’t stick up (the bottom keys) to form a pattern that matches the contour of your hands.

In order to represent the shapes, the keyboard is segmented into repeating groups of keys that also match the shape of your hands. And it’s symmetrical, so each shape has its mirror image, just as your hands are mirror images of one another.

With a slight shift of perspective, you can see any standard keyboard in this way as well: Navigate the keyboard by touch alone, and there are no more black and white keys—only top and bottom keys. Center yourself at “Middle D,” and the keyboard becomes symmetrical. Imagine that it extends infinitely in either direction, and the compass of your instrument becomes a window into this endless pattern.

Thinking of the keyboard in this way also suggests some different ideas about music. “Middle C,” which is often the first note beginners are taught to recognize, no longer seems so prominent. The associations of white keys being the “easy” keys, and black keys being the “hard” keys disappears, and each shape becomes its own distinctive group of “easy” keys, that’s also easy to remember quickly.

All of these subtle shifts of perspective position the keyboard itself as the language we use to understand musical ideas at first. The distinctive position of a single key on the keyboard acts as a name for the note you’ll hear when you press that key. And the number and direction of top keys in a shape gives us a way to name the shape. This allows us to detach ourselves, at first, from what often feels like a complicated grammar of musical names, of sharps and flats, of enharmonics, so that we can focus on some of the principles that underlie these names.

One significant purpose for doing all this is that it makes the keyboard—and the musical system it represents—feel simple, approachable, and perhaps even friendly. It helps us focus on the aspects of music that are familiar, that are already part of our experience, even part of our bodies.

But making this start feel simple and friendly also sets us up to understand the musical system in a much more complex and nuanced way. Most often, efforts to see through the surface layer of musical grammar set aside the distinctive collections of notes that sound most familiar to us—the collections represented by shapes—in favor of a structural principle common to all these collections: a construction by whole and half steps, a chromatic musical system.

This is an attractive idea. On a guitar fretboard, for example, you can play a musical structure, and then slide your hand up and down the fretboard, holding your fingers in the same position, to play any transposition of that same structure. On the keyboard, each transposition would take you into a different shape, and you would need to adjust your fingers into the contour of that shape. Thinking of all the transpositions as the same structure would require an abstraction of the structure from any instantiation of that structure on the keyboard.

Innovations to simplify music notation likewise tend, in one form or another, to reframe the staff that represents the collection of notes in a shape to a chromatic staff. By doing this, any notated musical structure will look the same, no matter where it is transposed on the staff. Sometimes this approach to notation is aligned with a chromatic view of the keyboard, as in the piano roll notation often used in music production software, and in scrolling instructional videos patterned after rhythm games. It removes the complications of notational grammar.

More recently, an increasing number of electronic musicians have begun to play and represent pitch material on grid controllers, typically an 8-by-8 matrix of buttons or pads that evolved from early drum machines and step sequencers. This is an even more striking expression of the trend to abstract an evenly transposable, chromatic principle from the musical system. Groupings of pads can be assigned to a particular musical scale, a construction of whole and half steps, or to represent the underlying chromatic structure directly. The result is an instrument interface that also serves as a representation of a chromatic musical system. It feels rational, intelligible, and therefore simple and approachable.

But instruments, diagrams, and concepts that present a chromatic musical system also suggest that musical structures, and contexts like those represented by shapes, are built up from the basic units of the chromatic scale. Shapes takes a different view. In Shapes, the simplest meaningful unit is the collection of notes represented by the shape, because this is where the concept aligns with our musical intuitions. A chromatic system comes about only as an abstraction from the overlap of these collections of notes. Whole and half steps don’t exist in advance of this abstraction, and so the collection of notes in a shape are not composed of whole and half steps.

Furthermore, taking the shape as a basic unit makes the interplay of collections of notes in our musical system intelligible. The relationships between individual notes always remain connected to a larger context. This feels simple and approachable because it represents our intuitions about music in a way that a grid of evenly-spaced, chromatic notes can not. Each shape is distinctive—visually, tactilely, and sonically—and this is what brings it into a meaningful relationship with other shapes, and with the musical system at large.

The subtle shift in how we approach the keyboard for Shapes is meant to capture these priorities, to be inviting, and to convey that our musical system is intuitive, intelligible, and approachable, all in a single, playable glance.